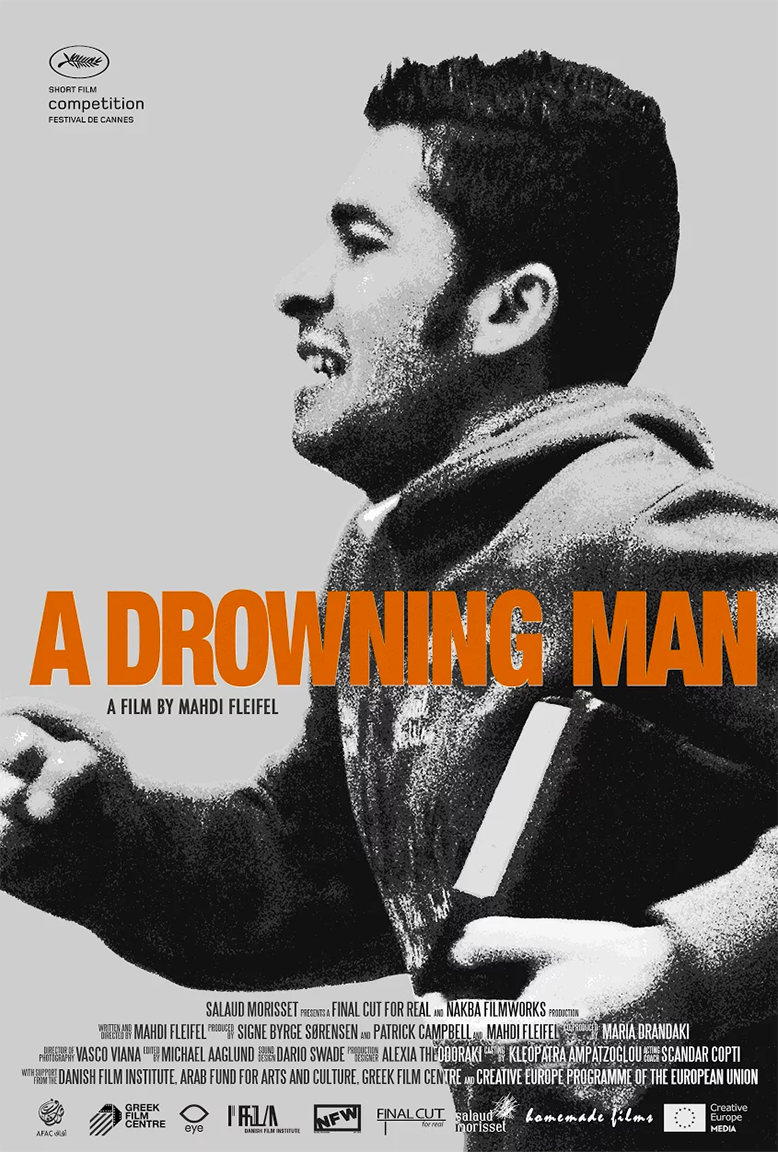

Directed by Mahdi Fleifel –

Fatah makes his way through the streets of modern day Athens trying to find enough money to get by. On his travels he encounters the wisdom and desperation that permeates this place and defines his existence.

GFM: In A Drowning Man, your main character, ‘The Kid’, is a Palestinian living in Athens with no money. He is an outsider in this society and trying to survive. What inspired you to tell this story and how does it fit into the context of the rest of your work?

Mahdi: In a way I would say A Drowning Man is a fictional adaptation of a film essay I did called Xenos (2014), which was the epilogue to my feature documentary, A World Not Ours (2012). It’s a story I conceived through following my lead character, Abu Eyad, from A World Not Ours and Xenos. I discovered many of these young men who were living in Greece with no documents, no papers, no money – basically nothing – and they were resorting to all sorts of means to survive, whether it was by selling drugs or themselves. I wanted to explore this in a fictional way. I’ve also been trying to raise funds for a feature film, which will be my first fiction feature. Given that I’ve only made documentaries since I graduated, despite the fact that I graduated as a fiction director from film school, I wondered whether I could still do fiction. So, my motivation was partly to tell this story, and also to see whether I could still direct a fiction film.

GFM: Considering your previous films A World Not Ours and A Man Returned (2016) also deal with the lives and challenges facing Palestinian refugees, please could you talk a little bit about this recurring theme and its progression in your work?

Mahd: For me, it seems like the most obvious thing as a storyteller to tell my own story. I came to Denmark from the Middle East as a refugee with my family when I was nine years old, so it’s always been a big part of my life. I’ve lived in Europe for most of my life now, but the refugee aspect has always been prevalent. Most of my family still live in refugee camps. My grandfather, who is 85, has lived in the Ain El-Helweh refugee camp in Lebanon since 1948, as a result of the establishment of the state of Israel. It’s something that is very personal to me, and I feel a certain necessity and responsibility to share it with the world.

As I am Palestinian, I relate to Palestinian men and can easily communicate with them. But it’s the same deal for Syrian, Afghan, Pakistani or Iranian refugees. Looking back at the work I’ve done since A World Not Ours, I’m more interested in guys my age and what they’re having to go through in order to obtain the most basic things in life, whereas in a way, I was privileged. I came here in the ’80s at a young age and I was able to learn a new language, get an education and a passport, which allowed me to travel freely. However, I seem to have an obsession with the masculinity crises, if you will, among these young men, more than with a specific Palestinian narrative discourse.

GFM: Our readers are always interested in how projects come together. What was the journey of the film from conception to production to Cannes, and how did you secure funding?

Mahdi: I generally find that one story leads to another. In A World Not Ours I followed my main subject, Abu Eyad, who brought me to Athens as a result of his leaving the camp in Lebanon and going to Greece. When I found out what was going on in Greece, it led me to the story of Xenos. A Man Returned was about another young man I was following in Athens, but he was deported to the camp in Lebanon. And so it continues. Thematically, it’s an organic process. I move onto the next obvious thing as these stories progress.

Regarding the funding for A Drowning Man, this was a last minute thing. I was in New York last summer and I wrote the script very quickly with the intention of going to Greece to do a casting workshop. It was intended to test out what it would be like to cast real refugee men in Greece and work with them in a fictional context, including working a local Greek crew. Rather than set out to make a short, which would stand on its own, the idea was more about doing a workshop to test things out.

We then applied for and were given a small grant from AFAC, which is the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture. That led us to some more funding opportunities, specifically from the Danish Film Institute, which was a honey pot I had been trying to get my hand into for years. One of the documentary consultants was a fan of A World Not Ours. She believed in me and the story and gave us a development grant in February. It was at that point that I found these boys and in March we began shooting and editing simultaneously, after which we attempted to get the film into Cannes It was a long shot, but after cutting the film they told us that it had been selected. It was an intense process, which took about three months. Of course, the Danish Film Institute is thrilled as I am the only Dane in competition in Cannes this year.

GFM: Speaking of your team, I believe this is your fourth co-production with Patrick Campbell?

Mahdi: Patrick and I have a company together (Nakba FilmWorks), which we set up in 2010. He’s my partner in crime when it comes to film. Together we produce everything I write and direct. Then we had a Danish producer, Signe Byrge Sørensen, who did The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence. She also comes from a strong documentary background, which she combines with the world of fiction, which is the way I wanted to work. We also had a wonderful Greek producer, Maria Drandaki, from Homemade Films, who facilitated the entire production in Athens and brought on board a fantastic local crew and a Greek casting director who helped me find the men in the refugee camps. I had a cinematographer from Portugal, Vasco Viana, who’s done amazing work with Joao Salaviza. Dario Swade did the sound design – he’s British and we went to film school together. My editor, Michael Aaglund, is Danish, and Patrick is Irish. So it’s a true European co-production.

GFM: Lastly, what does it mean to you to have the film going to Cannes In Competition?

Mahdi: It means racing against time to finish the film and trying to make it look and sound as good as possible. It’s really exciting. There’s a sense of sweet victory that we had set out to do this as a test as to whether we could make a fiction film. I hope this will prove to skeptic financiers that if we managed to do this in such a short time, we could probably pull off a solid feature. I think it’s given our team the confidence in moving forward to make the big one.

director Mahdi FLEIFEL